Subtotal $0.00

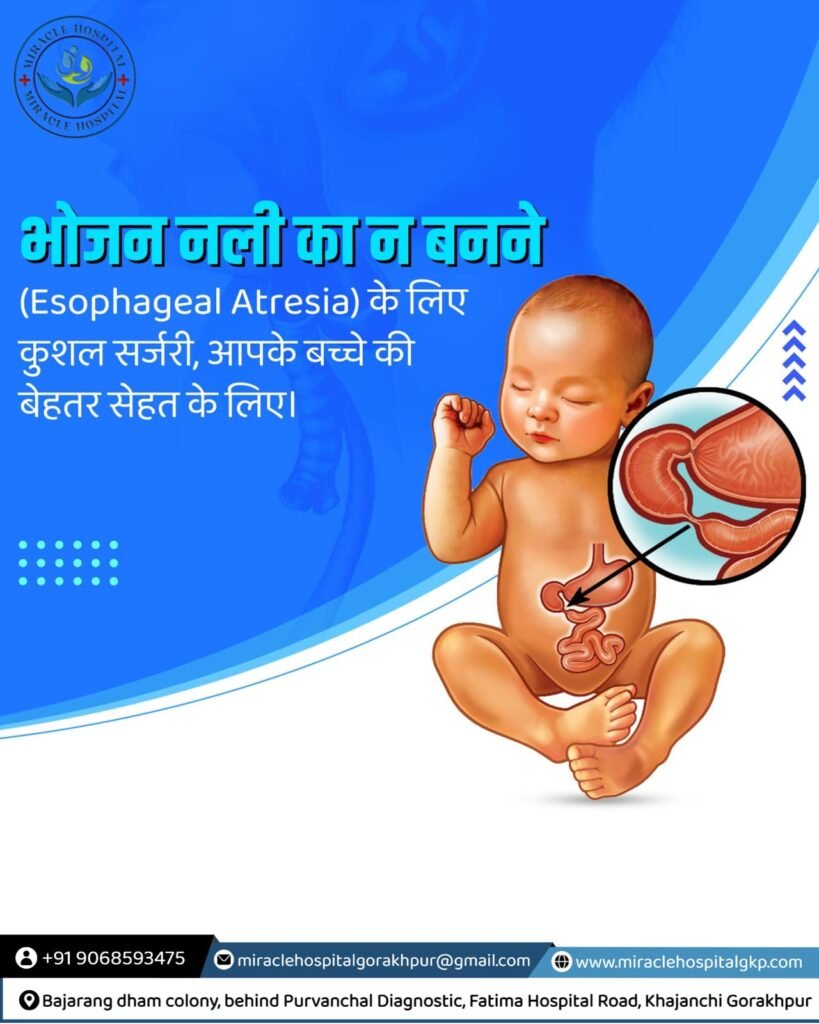

Esophageal Atresia: Understanding, Diagnosing, and Treating a Complex Pediatric Condition

Introduction

Esophageal atresia (EA) is a congenital condition where the esophagus, the tube that carries food from the mouth to the stomach, does not develop properly. This rare disorder affects approximately 1 in 4,000 live births and requires immediate medical attention and surgical intervention. Understanding the complexities of EA is crucial for early diagnosis, effective treatment, and better outcomes for affected infants.

Anatomy and Types of Esophageal Atresia

In a normally developed esophagus, a continuous tube connects the throat to the stomach. However, in esophageal atresia, the esophagus is incomplete. There are several types of EA, classified based on the location and nature of the atresia and any accompanying fistulas (abnormal connections) between the esophagus and the trachea (windpipe).

- Type A (Pure Esophageal Atresia): The esophagus ends in a blind pouch at both the upper and lower ends, with no connection to the trachea. This type accounts for about 8% of cases.

- Type B: The upper esophagus ends in a blind pouch, while the lower segment forms a fistula with the trachea. This type is extremely rare.

- Type C (Esophageal Atresia with Distal Tracheoesophageal Fistula): The most common type, occurring in about 85% of cases, where the upper esophagus ends in a blind pouch, and the lower segment connects to the trachea.

- Type D: Both the upper and lower segments of the esophagus form fistulas with the trachea. This type is very rare.

- Type E (H-Type Fistula): The esophagus is continuous, but there is a fistula between the esophagus and the trachea, without atresia. This type accounts for about 4% of cases.

Causes and Risk Factors

The exact cause of esophageal atresia is not fully understood. However, it is believed to result from abnormal embryonic development of the esophagus and trachea during the fourth to sixth weeks of pregnancy. Certain factors may increase the risk of EA, including:

- Genetic mutations and chromosomal abnormalities

- Maternal exposure to certain drugs or environmental toxins

- Family history of EA or other congenital anomalies

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Newborns with esophageal atresia typically exhibit symptoms soon after birth, which may include:

- Excessive drooling and salivation

- Choking, coughing, or gagging during feeding

- Difficulty breathing

- Cyanosis (bluish skin color due to lack of oxygen)

- Inability to pass a nasogastric tube into the stomach

Diagnosis of EA is confirmed through imaging studies such as:

- Chest X-ray: Reveals the presence of a blind-ending esophagus and possible air in the stomach (suggestive of a tracheoesophageal fistula).

- Contrast esophagogram: Involves the introduction of a contrast agent into the esophagus to visualize its anatomy and any fistulas.

Treatment and Surgical Intervention

The primary treatment for esophageal atresia is surgical repair, typically performed shortly after birth. The specific surgical approach depends on the type and severity of EA. Common surgical procedures include:

- Primary Anastomosis: The two ends of the esophagus are brought together and sutured. This is the preferred approach for types A, B, and C.

- Esophageal Replacement: In cases where the gap between the esophageal segments is too large, a segment of the colon or stomach may be used to replace the missing portion of the esophagus.

- Tracheoesophageal Fistula Repair: For types D and E, the fistula is closed to prevent aspiration and improve swallowing function.

Postoperative Care and Long-term Management

After surgery, infants require careful monitoring and postoperative care to ensure proper healing and prevent complications. This includes:

- Nutritional Support: Initially provided through intravenous fluids or a gastrostomy tube, transitioning to oral feeding as tolerated.

- Respiratory Support: Monitoring and managing any respiratory issues, especially in cases with associated tracheomalacia (weakness of the tracheal walls).

- Regular Follow-up: Lifelong follow-up is essential to monitor growth, development, and potential complications such as gastroesophageal reflux, esophageal strictures, and feeding difficulties.

Prognosis and Outcomes

The prognosis for infants with esophageal atresia has improved significantly with advances in surgical techniques and neonatal care. Most children with EA can expect a good quality of life, though some may require additional interventions and ongoing medical support. Early diagnosis, timely surgical intervention, and comprehensive postoperative care are critical to achieving the best outcomes for these patients.

Conclusion

Esophageal atresia is a complex congenital condition that poses significant challenges but can be effectively managed with prompt diagnosis and appropriate surgical treatment. Advances in medical science continue to improve the prognosis and quality of life for affected infants, offering hope to families facing this difficult diagnosis. Continued research and clinical expertise are essential to further enhance our understanding and management of this condition, ultimately benefiting the youngest and most vulnerable patients.